For many years, Yoruba cinema has been inspired by the mystical realm of witches, warriors, and traditional figures. These characters, depicted vividly, have shaped a genre and made the boundary between acting and belief unclear. IBRAHIM ADAM states that behind these strong roles are actors whose lives embody sacrifice, social disapproval, strength, and devotion, showing that what is seen on screen often extends well past the screen.

AcrossYoruba cinema has been more than mere entertainment in Southwestern Nigeria, other regions, and even among the diaspora. It serves as a reflection of societal values, a guide for ethical conduct, and sometimes a haunting reminder of the hidden forces that people dread.

For many years, witches, warlords, and traditionalists immersed in the supernatural have been central to its narratives, establishing a unique place in the history of Nigerian cinema.

The power of these shows captivated viewers, making it hard to distinguish between what was real and what was imagined.

Certain actors were regarded as symbols of enigmatic strength, whereas others faced mockery, distrust, or individual spiritual struggles due to the parts they portrayed.

Some of them include veterans such as Ato Aseku, Lalude, Alapini, Alebiosu, and Iya Gbonkan, who continue to be remembered as living examples of this complicated blend of faith and action.

Their paths highlight not just the efforts of early innovators who established the supernatural elements in Nollywood, but also the challenges they faced and the lasting impact they created.

Ato Aseku: The weight of donning the witch’s visage

In a peaceful town located in Oyo State, Adeshina Rafatu, who would eventually become well-known, lost both parents at a young age. Although life appeared to guide her toward the sewing machine she had become skilled at, fate had different intentions, leading her to discover her voice and direction in the Yoruba film industry, where she gained fame under the name Ato Aseku, a name remembered by many generations of movie enthusiasts.

For viewers who were raised watching Yoruba films in the 1980s and 1990s, Ato Aseku was more than just an actress; she represented the essence of enigma and threat. Her portrayals as a formidable sorceress were so vivid, so profoundly disturbing, that they remained with audiences even after her character’s story concluded.

To many, she represented the essence of the paranormal; a being to be dreaded, honored, and never erased from memory.

Rafatu was born on 25 March 1959 in Ipapo, located in the Itesiwaju Local Government Area of Oyo State, within the Oke-Ogun region, and her life narrative is marked by perseverance and transformation.

She is much more than a seasoned actress; she is a living repository of Nollywood’s history, a guardian of Yoruba cultural narratives, and a source of motivation for future actors.

However, her skill came with a price. The boundary between imagination and truth was frequently unclear, and she carried the burden of society’s failure to distinguish the actress from her characters.

Rafatu still remembers a moment of shame that caused wounds more profound than language.

“I was publicly labeled as a witch. This role significantly impacted my life and how people viewed me in society. I’ve found myself in situations where my clothing was ripped in a public area, and everyone began to call me a witch while laughing at me,” the experienced actor said, her voice slightly shaky.

Even though she faced mockery, Rafatu remained steadfast in her beliefs. As a committed Muslim, she stood by her work when others wondered why she depicted witches in her films.

Many people have questioned why I portrayed a witch even though I am a Muslim. I felt that all the films in which I played such roles were intended to convey important life lessons, she explained.

For her, these roles served as lessons on ethics, rather than approvals of the supernatural realm.

The steadfast admiration of her family for her work served as a sanctuary during difficult periods.

“My family never responded negatively. Rather, they were consistently pleased and proud to display me in public,” she mentioned.

However, the comfort of family could not protect her from the hostility of strangers who ridiculed and looked down on her, and could not distinguish between reality and acting.

Rafatu’s initial experiences within the Yoruba film industry were filled with challenges. Entering the cinematic world during the 1970s and 1980s, she faced a setting that was unpredictable, unfair, and economically uncertain, where anticipated payments frequently disappeared without a trace.

“I had an agreement with the movie directors regarding my payment, but I was often deceived after performing my roles, and at times, I wasn’t paid at all,” she remembered.

The battle was not solely about money. Physical challenges became a regular part of life. Nights without a place to stay compelled her and her coworkers to think creatively.

“After a long day of work, we wouldn’t have anywhere to rest. The only choice was to unfold our coverings and lie down outside,” Rafatu said.

Throughout various stages, the burden of difficulties almost made her leave the industry. However, her late husband, Ganiu Adebisi Adegboye, who was also an actor, served as her source of support.

I encountered numerous difficulties as a young woman. There were many issues that made me consider leaving the field, but my late husband encouraged me to continue.

From a retrospective view, Rafatu considers the difference between her generation of performers and the younger ones currently active.

She smiled sarcastically, saying, “In terms of earnings, the current era offers more than the past. Back then, there were many questionable activities where we would work all day without receiving any payment.”

Still, she holds no resentment. Her love for acting is undiminished, although her eyes now look toward filmmaking.

I would also like to create a film once I’m in a better financial situation to cover the expenses. Producing is something I could focus on with the help of funding.

She views the path of today’s actors as much less dangerous than her own.

Regarding the younger generation, I don’t believe they encounter as many difficulties as we did since everything appears to be simpler and more straightforward. They have more chances available to them—even the smaller ones are accessible to opportunities.

For Rafatu, Ato Aseku, the title of witch turned into both a burden and a symbol of honor. Although she faced mockery in public, her performances on screen left an unforgettable legacy in the annals of Yoruba cinema.

Lalude: The warlord as an entertainer, not a predator

If Ato Aseku endured the disgrace of being labeled a witch, Fatai Adetayo, widely known as Lalude, carried his supernatural roles with steadfast dignity.

His username is intended to represent warlords, traditionalists, and individuals whose chants resonate throughout the Yoruba film industry.

For many years, he has been seen as the representation of Yoruba religious beliefs. However, he claims that his acts are simply well-designed stage performances.

Assuming the role of a witch or warlord is not something we do permanently. The witchcraft depicted in Nigerian films is not authentic. True witches are different; you can’t even look them in the eye. You talk about witches? Who has the courage to look at them or act as they do? When a statement is incomplete, it doesn’t make sense. Therefore, what we portray on screen is merely a performance.

In contrast to Rafatu, Adetayo has never faced public criticism for his performances. Instead, fans love him.

I have never encountered any negative, difficult, or disrespectful treatment in my life. Instead, people value me for my work. They smile and say, ‘Lálùdé ògùn, Akápò òògùn,’ because they appreciate what I do.

His skill was developed in Yoruba theater, after many years of training and stage work.

He gained experience with the Oluwole Concert Party in Shogunle, later became part of the Ademola Theatre Group in Lagos, and eventually established his own group in Ibadan— the New Vision Theatre Caucus.

Via these platforms, Adetayo learned spells, refined the authoritative demeanor of warlords, and developed the presence of a traditionalist that would eventually shape his on-screen persona.

Nevertheless, filmmakers frequently limit him to these types of roles.

They often typecast me in conventional roles instead of contemporary ones. In modern movies, I also portray an Ifá priest (babaláwo). However, the casting choices are influenced by the producer. Due to their perception of me, even though I am capable of taking on various roles, this is what I excel at. That’s why they frequently cast me as a warlord or babaláwo.

For Adetayo, acting has not remained static; it has progressed alongside time and technological advancements.

What we did in the past was related to the circumstances of that era. Our current actions are different due to advancements in technology. The technological progress today is more significant than what we had before. There have been improvements in technology, and it also contributes to enhancing our character.

Where spectators perceive magic and enchantments, Adetayo views scripts and theatrical techniques. His shows are not calls to the supernatural but demonstrations of the skill in Yoruba film.

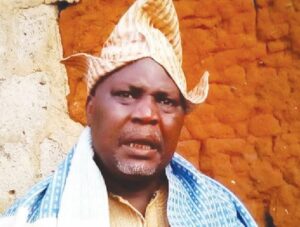

Alapini: The Keeper of Spells

Ganiu Nafiu, also recognized as Alapini, has been a central figure in discussions within Yoruba cinema.

Viewers are amazed by the strength of his incantations, believing they reflect genuine magical energy. However, the performer swiftly refutes these concerns, stating that what spectators hear is simply theatrical entertainment.

“The spells we use in acting cannot cause any harm. There is something known as a chant, or perhaps I should call it ayajo, ohun Ife, which is simply a statement that should not be heard by anyone else. However, if this statement is incomplete, it has no effect. If we do not recite them properly, they cannot harm anyone or fulfill their intended purpose,” he explained to Sunday PUNCH.

For Nafiu, the act concludes once the camera ceases filming.

Any spell featured in the film remains within the movie and poses no threat to us. Although they may sound authentic, they are incomplete. How could they cause any harm?

Although he is well-known for his traditional roles, Nafiu has expanded his acting into various characters: pastor, police officer, armed thief, and even a source of humor. However, he admits that casting decisions follow an unwritten pattern.

It’s impossible for a producer to request me to take a role intended for Odunlade Adekola since it wouldn’t be effective. Moreover, if Odunlade were to assume my role as a traditionalist, it wouldn’t be the same.

His path is strongly connected to the Yoruba theater tradition. He studied under the famous Kola Ogunmola, whom he highly respects as an expert in traditional roles.

His ancestry also connected him to tradition, as both his father and grandmother were recognized as keepers of native healing methods.

Nevertheless, Nafiu distinguishes religion from imagination.

We are Muslims, and I attended a Madrasa (Arabic school) for some time. Faith resides in the heart. Therefore, religion is separate from my career in acting.

He remembers a period when Nollywood faced significant negative perception.

Back in those days, it was rare to find a parent who supported their children pursuing a career in acting. Women, in particular, were often labeled as prostitutes for entering the industry, while men were seen as lazy. However, those of us who recognized its potential for profit took the plunge, and now it’s a field that everyone is eager to get involved in.

However, the sector continues to face its disparities. Nafiu points out the issues surrounding compensation.

Payment is tied to status. Many producers invest in recognizable names, just as audiences have their preferred actors and actresses. Even if there are individuals who can perform the roles effectively, producers may still choose the well-known faces to boost the film’s appeal. Therefore, your role doesn’t dictate what you receive. It depends on your level of recognition.

Alebiosu: When Filmic Chants Invite Actual Nightmares

If Nafiu claims that incantations are just performances, Adewale Alebiosu, referred to simply as Alebiosu, presents a more disturbing account.

Renowned for portraying Ifá priests, he found that narratives intended as fiction occasionally led to significant consequences.

“I had no idea there was so much more involved in the spells I was reciting. I believed I was simply speaking my lines, unaware of the consequences,” he admitted.

The outcomes manifested as frightening nightmares.

“After finishing the filming, while I was asleep, I would encounter unusual creatures. Some transformed into goats and began to bite me. I’m sharing this so that people don’t come to regret their lives or face a tragic end,” he cautioned, advising young actors to be spiritually vigilant before taking on such roles.

In addition to the nightmares, being typecast caused confusion between his public image and real life. Some believed he was a local healer, a statement he strongly denies.

“People often see me as one, but I’m not. My parents are Muslims,” he explained.

Alebiosu’s professional journey started under Taiwo Balogun and later Fatai Adetayo (Lalude), where he developed expertise in roles requiring powerful chants, which producers frequently offered him. However, a significant change occurred during a church harvest event: while playing the drums, he entered a trance. This experience led him down a new path as a Christian minister.

Currently managing his roles as both an actor and a minister, Alebiosu states that his on-screen recitations are merely part of his acting, although he admits that the words can occasionally hold secret powers.

Sure, here’s a paraphrased version of the given text: “Iya Gbonkan: The Unforgettable Image of Yoruba Horror”

Foremost is Bamidele Olayinka, widely recognized as Iya Gbonkan, the individual whose intense gaze, distinctive facial structure, and powerful demeanor both frightened and captivated viewers over many years.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, her intense gaze had the power to quiet a room, establishing her as the iconic figure of Yoruba horror films.

She turned the intimidating roles that once troubled her into a testament of strength, creativity, and belief.

Born in Otu and Iseyin, Olayinka emerged from modest origins to become a prominent figure in Yoruba film.

Her major success was in 1989 with Koto Orun, an occult thriller directed by the late Yekini Ajileye.

The movie solidified her status as the personification of Yoruba horror, a performance so authentic that many found it hard to distinguish between the fictional narrative and real life.

But recognition brought conflicts.

Olayinka told Sunday PUNCHthat her part in Koto Orun drew not only praise but also spiritual assaults.

“They attempted to make me shed and consume blood, yet I refused. It is not part of my heritage to engage in such acts. I endured their assaults, even when they struck me while I was asleep and damaged my face. Things turned dire after Koto Orun, but God supported me due to my truthfulness. I could have perished during Koto Orun, but God kept me alive,” she said with a smile.

Olayinka shared that each actor involved in the project faced challenges.

The difficulties we encountered during that time are hard to describe, and I wasn’t the only one who experienced them. I am grateful that we managed to get through them, as everyone involved in the production had their own struggles. For me, I would pray before stepping onto the set and pray once more after leaving, because it was never simple to portray those characters.

Even with the negative perception, Olayinka maintained that she did not acquire any witchcraft skills from anyone.

I didn’t acquire it from anyone. I simply have a passion for my work. When it comes to acting, I simply perform the script. Every actor does that, but it’s up to us to bring our abilities to interpret it effectively.

Her professional journey, nevertheless, has not been limited to witch characters, as she confidently highlights her range, particularly in recent comedic sketches.

I am capable of playing any role. I have portrayed a prayer warrior, a mother-in-law, and even a wife. Commitment to your profession is what sets you apart. The witch roles gave me attention, but through skit videos, people now recognize my diverse abilities.

However, she recognized the significance of genuine spells in Yoruba movies.

Those things are genuine. At times, it’s necessary to pray before uttering any spell. There are numerous ones I would never attempt, as if you try, something different might occur. Many of my peers also refrained from completing them for the same reason.

For her, performing has always been more than a job; it is a vocation.

“Since God stated that He would elevate me through my actions, I committed myself to it. I am a Christian, and when you have God, you possess everything. If you align yourself with God, regardless of the obstacles, you will overcome them. There was a period when individuals asserted that I was part of a witch cult due to my roles. I simply smiled, as that is not true. Our sole purpose is to act for financial gain, not to be involved in something I am unfamiliar with,” she mentioned.

The depiction of Ifa priests in Nollywood is a complete distortion

Internationally recognized Ifá priest, writer, and scholar Ifayemi Elebuibon has consistently spoken out against Nollywood’s common misdepictions of Ifá priests.

He explained that a babalawo is not a fetish or a sorcerer, but rather a diviner and healer, holding a spiritual title that is attained only after nine years of intense training to become proficient in the 260 oral literature scriptures called Odu Ifa.

“Those who write plays for Nollywood today have nothing meaningful to show about babalawo (native doctor) on screen. The way they portray babalawo is incorrect. Babalawo is not an herbalist but a priest, one who heals the broken world,” he explained.

He believes that Nollywood’s long, emotional speeches are not needed. In fact, a few well-chosen sentences suffice. He encouraged screenwriters to thoroughly understand Odu Ifa before creating such characters.

He insisted that the way Nollywood is depicting Yoruba culture is insufficient.

Elebuibon commended earlier groups of playwrights like Duro Ladipo and Hubert Ogunde, whom he noted based their creations on research, discussions with elders, and genuine tradition.

“Individuals today are unmatched,” he said, full of sorrow.

The scholar also tackled misunderstandings that connect ceremonial customs with financial status.

He stated, ‘Money would consistently appear via work-related, career-oriented, and craft-based activities.’

Justifying the use of sacrifices in Ifa, he drew parallels to rituals found in other faiths:

A child of God claimed he has saved the world through his blood. In certain sacred texts, you can find accounts of animal sacrifices. Ifa does not involve human blood, if that is what individuals believe.

They deserve recognition for their expertise in the roles

Yoruba film producer, Kunle Afod, has praised actors who are well-known for playing roles such as witches, warlords, and traditionalists, calling them skilled professionals whose work has gained them admiration within the film industry.

He observed that the discipline and adaptability of these actors made them exemplary figures, as they manage a rigorous profession alongside solid spiritual principles.

“Many of them are devoted to prayer, and they pray frequently. For example, Ato Aseku is a committed actress. She was married to an actor, and without her commitment, I don’t believe many women would choose to marry an actor while also working in the same field. They have all put in a lot of effort in the industry, and I ask God to keep blessing them for their work,” Afod said.

The director highly praised the actresses for bravely embracing challenging roles, particularly in films centered around witches, which have shaped their professional paths.

When it comes to portraying a witch, if you are a skilled performer, whatever part you are assigned, audiences will accept you as that character.

If you refer to me as a snitch or a armed thief in a film and you observe me with a gun, does that imply that’s my profession? “No,” he clarified.

As he stated, the skill of these artists in authentically portraying such roles not only elevated many of them to prominence but also reinforced their standing.

“Back then, it was Ajileye who created more movies about witches, warlords, and traditionalists, which most of them began with. That is why many of them fit into those roles very well. They have a better understanding of those roles and can manage them effectively,” he added.

Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (

Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. ( Syndigate.info

Syndigate.info ).

).

Leave a comment