The Nobel Prize is often referred to as the “Mount Everest of science.” However, it has come under scrutiny for its selection process and might present a distorted view of scientific advancement.

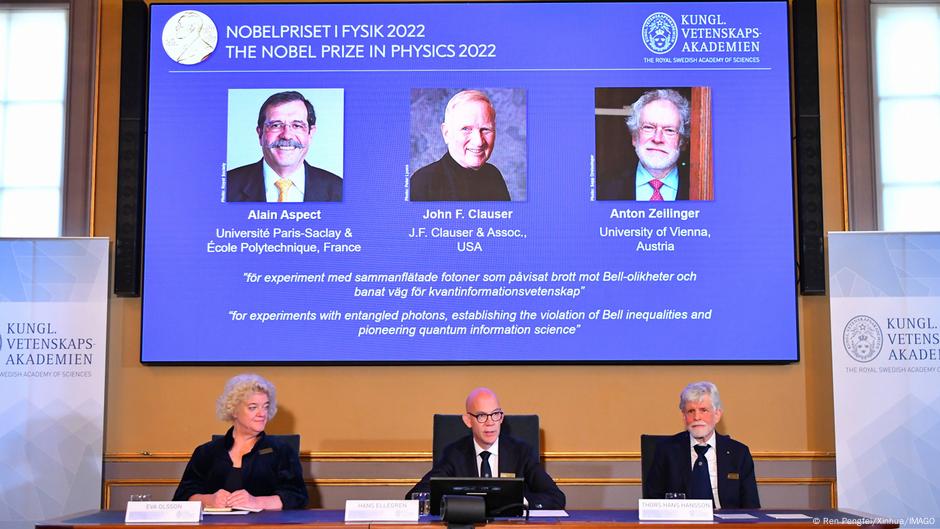

Each October, a few scientists are awakened by a phone call informing them that they have been awarded a Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, physics, or chemistry.

Surprised and with tired eyes, they quickly put a shirt over their pajamas, hop on a video call to Stockholm, and attempt to convey a lifetime of research to the global media in just a few minutes.

Journalists then urgently attempt to grasp what “quantum dots,” or “entangled photonsare, submit their reports, and then feel a sense of relief that it’s all done until next year. By the following week, everyone has moved on—another brief moment in an ongoing stream of news.

Be honest, who really cares about Nobel Prizes? Are these prizes, first awarded in 1901, with all their high-class pomp and ceremony, still relevant today?

The Nobel Prizes contribute to increasing public awareness of scientific advancements. However, do they also create a misleading view of the discovery process? Are they excessively inclined towards supporting science from the United States, Europe, and male researchers?

Noble idea behind the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes began with the last will and testament of a scientist filled with remorse —Alfred Nobel, the creator of dynamite.

Nobel’s goal was to reward outstanding science to “those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.”

Nobel Prizes represent significant achievements in scientific progress. They acknowledge the efforts that have safeguarded millions of individuals from serious COVID-19 infections.rapid vaccine development, the development of energy-efficient LED lighting andgene-editing technologieswhich have healed diseases that were once untreatable.

“It’s certain they are the Mount Everest of science. The Nobel Prizes represent the peak of scientific achievements, and there is a strong emotional connection to them,” said Rajib Dasgupta, a doctor and professor of public health located in New Delhi, India.

At the very least, the awards serve as a reminder that we are lucky to reside in an era marked by recent scientific breakthroughs, following discoveries like DNA, vaccinations, and concepts regarding the Big Bang and subatomic particles.

Do the Nobel Prizes truly motivate individuals towards science?

The Nobel Prizes can effectively spark public interest in science by being showcased through mass media.

The degree to which media organizations report on the Nobel Prizes differs across nations, but Dasgupta mentioned that the Indian media closely follows the awards — and in depth, rather than merely for news updates.

“The interest stems from an increased focus on STEM fields in India, especially within the middle class,” Dasgupta mentioned, referring to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

Incorporating lessons on the Nobel Prizes into the Indian school curriculum aims to spark public interest in science, similar to efforts seen globally.

Lily Green, a biology instructor at a secondary school in Newbury, UK, for students aged 11 to 18, mentioned that she included a historical view of the Nobel Prizes in her science lessons, though she didn’t track the award announcements each October.

“We employ them to instruct on the core principles of science. The most remarkable discoveries are those that spark children’s interest through scandals or compelling narratives — such as [Barry Marshall], who infected himself with bacteria to demonstrate how they lead to ulcers,” stated Green.

However, Green questioned if the Nobel Prizes significantly motivated students to pursue science at the university level.

“They are typically fascinated and engaged with science, not because they aim to win a Nobel Prize,” she said.

The Legend of the Brilliant Scientist

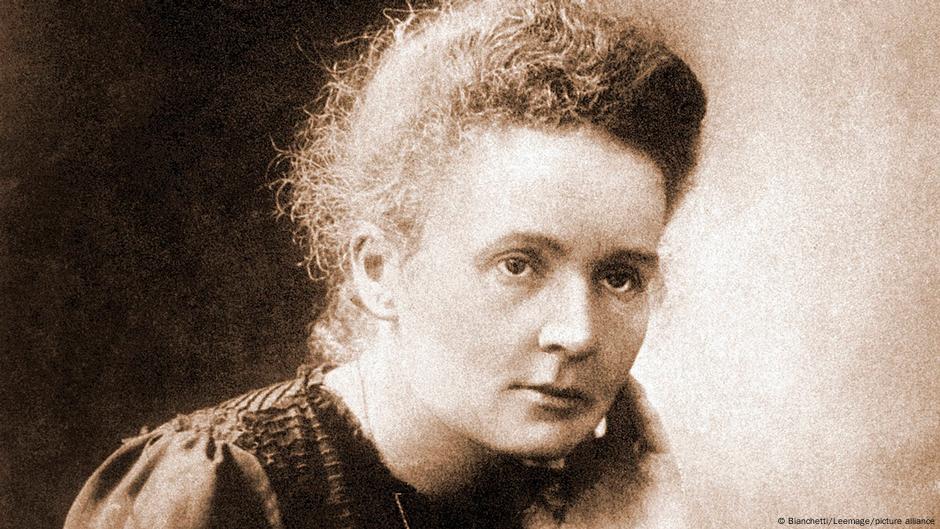

In the initial years of the Nobel Prizes, they were primarily given to male scientists, such asAlbert Einstein or Rutherford.

The gender of Marie Curie — in terms of the proportion of male to female scientists — was, and remains, unique. However, Curie received two Nobel Prizes, making her a dual exception.

The awards contributed to the concept of the brilliant scientist — an individual who independently advanced science through their exceptional intelligence.

However, in practice, scientific advancement functions quite differently, particularly in modern research.

Breakthroughs in science emerge through partnerships involving hundreds of scientists globally across various disciplines. Science represents a collective effort — it is interdisciplinary and inclusive.

Today, Nobel Prizes are often awarded to groups of scientists. However, for each Nobel winner, there are thousands of other scientists, Ph.D. students, and technicians who contributed to the research — and conducted the experiments — yet remain unrecognized, at least in the eyes of the general public.

Green acknowledged that there is a tendency to exaggerate the contributions of individual scientists in the Nobel Prizes, yet also believed that the concept of the lone genius scientist is becoming less prevalent.

“We are increasingly emphasizing that science is a team effort. It helps children understand the amount of work involved in scientific breakthroughs,” she said.

Insufficient representation in Nobel Prizes

The most significant critiques of the Nobel Prizes focus on their insufficient representation and preference for Western scientific organizations.

In the field of science, fewer than 15% of Nobel Prize winners are female.

Only a small number of individuals from nations outside Europe and the United States have received a Nobel Prize in Science. The United States, United Kingdom, and Germany lead in the count of Nobel laureates, with a combined total of 468. China has eight Nobel Prize winners, while India has twelve.

“Many awards are well-deserved, yet they are not free from political influences. Several institutions across various nations are being ignored, such as those in India. Moreover, the Nobel Prize committees are certainly not as diverse as they should be,” stated Dasgupta.

The Nobel Prizes may also increase this disparity by channeling additional resources to organizations that have previously received awards and the associated prestige.

However, Dasgupta stated that the truth was that institutions in India and other regions needed to become more robust to rival the US or Europe — only then would these nations be able to retain the talent they have developed.

Edited by: Zulfikar Abbany

Update, October 3, 2025. This article was first released on September 30, 2024. It is being published again before the 2025 Nobel Prize announcements.

Author: Fred Schwaller

Leave a comment