Scientists have identified a particular area in the brain that could help explain why older individuals frequently experience a reduced sense of familiarity with their environment as they grow older.

Researchers at Stanford University examined more than a dozen mice, whose ages corresponded to humans between 20 and 90 years old.

As the mice navigated virtual reality environments, their brains’ medial entorhinal cortex activated specific neural patterns known as grid cells.

The medial entorhinal cortex, often referred to as the brain’s ‘global positioning system,’ regulates interaction between the brain’s memory region, the hippocampus, and the area responsible for cognitive functions, the neocortex.

Grid cells assist in forming mental “maps” of an environment, allowing mice and humans to become acquainted with a location.

The team discovered that when young mice explored a space, grid cells in the medial entorhinal cortex fired in clear, organized patterns. But in older mice, as routines changed, the cells fired chaotically, evidence that their spatial memory had begun to break down.

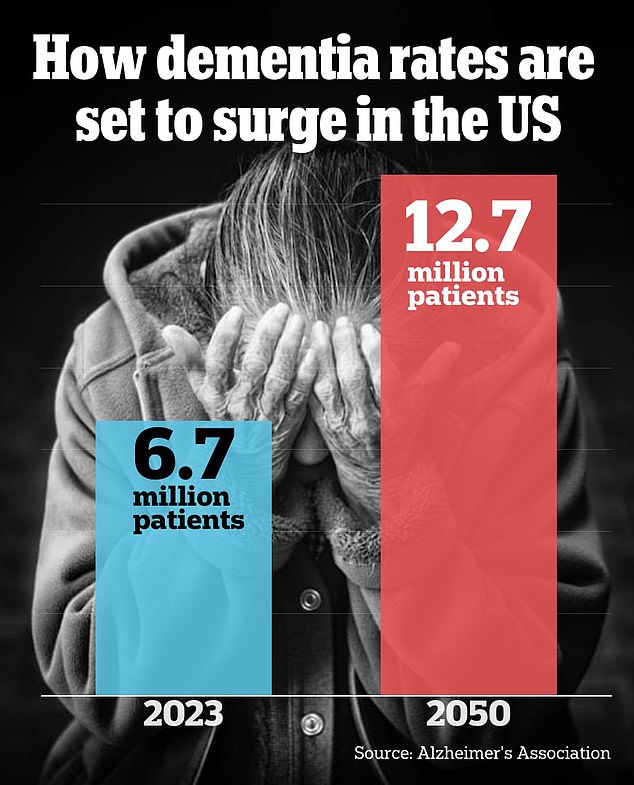

Memory of places or routes is significantly affected withtypes of dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease, indicating that the medial entorhinal cortex deteriorates as the disease progresses.

This may open the door to innovative therapies that directly focus on this particular structure.

Dr. Lisa Giocomo, the lead researcher of the study, who is a neurobiology professor at Stanford Medicine, stated: “You can imagine the medial entorhinal cortex as holding all the elements necessary to create a spatial map.”

Prior to this research, there was very little investigation into what occurs with this spatial navigation system as people age normally.

The research, released on Friday in the journalNature Communications, observed 18 mice categorized by age: three months, 13 months, and 22 months.

These periods correspond approximately to humans aged 20, 50, and between 75 to 90 years old.

Scientists captured the neural activity of mice that were mildly dehydrated as they navigated through virtual reality paths featuring a concealed reward, which consisted of a water sip.

The songs featured participants running on a stationary ball enclosed by screens showing a digital setting, which the group likened to a mouse-sized treadmill within a mouse-sized IMAX cinema.

For six days, the mice traversed the tracks hundreds of times. By the conclusion of the study, mice from every age group had learned the location of the reward on a specific track and only paused at the reward spots to lick.

As they learned the path, grid cells in their medial entorhinal cortex fired off distinct signals for each track, as if the mice were building custom mental maps.

But when mice were switched between two tracks they had already learned, each of which had a different reward location, elderly mice had trouble figuring out which track they were on.

Dr Giocomo said: ‘In this case, the task was more similar to remembering where you parked your car in two different parking lots or where your favorite coffee shop is in two different cities.’

This led the older mice to sprint through the rest of the track without stopping to search for rewards. Several even tried licking everywhere instead.

In the disoriented older mice, their grid cells activated unpredictably, rather than following the clear patterns they had developed once they became familiar with the paths.

Dr. Charlotte Herber, the primary researcher of the study and an MD-PhD candidate at Stanford Medicine, stated, “Their ability to remember locations and quickly distinguish between these two settings was significantly affected.”

Dr. Giocomo compared this to elderly individuals showing symptoms of cognitive deterioration or dementia.

She stated, “Elderly individuals typically find it easier to move around places they know well, such as their house or the area where they have always resided, but they struggle significantly when trying to learn to navigate a new location, even with prior experience.”

Nevertheless, younger and middle-aged mice could adjust to the changes, with their grid cell activity aligning with the track they were on in six days.

Herber stated: “From day one to day six, their spatial firing patterns become increasingly stable, and these are distinct for context A as well as for context B.”

The old mice are unable to form these distinct spatial maps.

Middle-aged mice exhibited somewhat diminished brain activity patterns, according to the researchers, although they typically showed comparable performance to younger mice.

Herber stated: “We believe this is a cognitive ability that remains functional at least until around 13 months in a mouse, or possibly between 50 to 60 years in a human being.”

The scientists mentioned that according to their results, older mice exhibited greater variation in spatial memory. Male mice also scored higher on the tests compared to female mice, although the research group is not certain about the reason.

The results indicate that the medial entorhinal cortex might play a role in assisting mice in preserving mental maps as they grow older and could be among the first areas to deteriorate in diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

The research received partial financial support from the National Institutes of Health.

- Unraveling the mystery: Why do busy streets offer better protection against Alzheimer’s than flying through the skies?

- Could a revolutionary protein finding in mice lead to the elimination of age-related memory decline in humans?

- Could your stomach be signaling early signs of Alzheimer’s? A pioneering study reveals the connection between the gut and brain, offering a potential way to anticipate memory loss years ahead!

- Are your brain’s signals indicating a potential future with Alzheimer’s, and might this be the clue to forecasting it?

- Have researchers recently revealed that your biological age could be the hidden factor behind your risk of dementia?

Leave a comment