Since the martial law crisis, a ‘far-right specter’ has appeared in South Korea’s political scene and public conversations. Media reports, surveys, and analyses that examine and stigmatize the far-right have become widespread. The so-called ‘far-right discourse’—which categorizes supporters of martial law, opponents of impeachment, the Seoul Western District Court incident, and anti-China demonstrations as far-right—has broadened to include social issues such as religion and minority groups. According to this definition, North Korea’s government, which opposes sexual minorities and intermarriage with immigrants, would be considered far-right. In contrast, Donald Trump, who appointed openly gay Scott Bessent as Treasury Secretary, would be labeled as far-left.

To explore the far-right, it is essential to first look at the core principles of left and right. The left emphasizes equality, with liberty serving as a secondary aspect; the right emphasizes liberty, with equality acting as a secondary concern. Opinions on human rights, the environment, and other topics vary based on the situation. Far-right and far-left ideologies represent groups that are prepared to resort to violence to defend these beliefs. Modern discussions overlook this distinction, broadly labeling everything as either far-right or far-left.

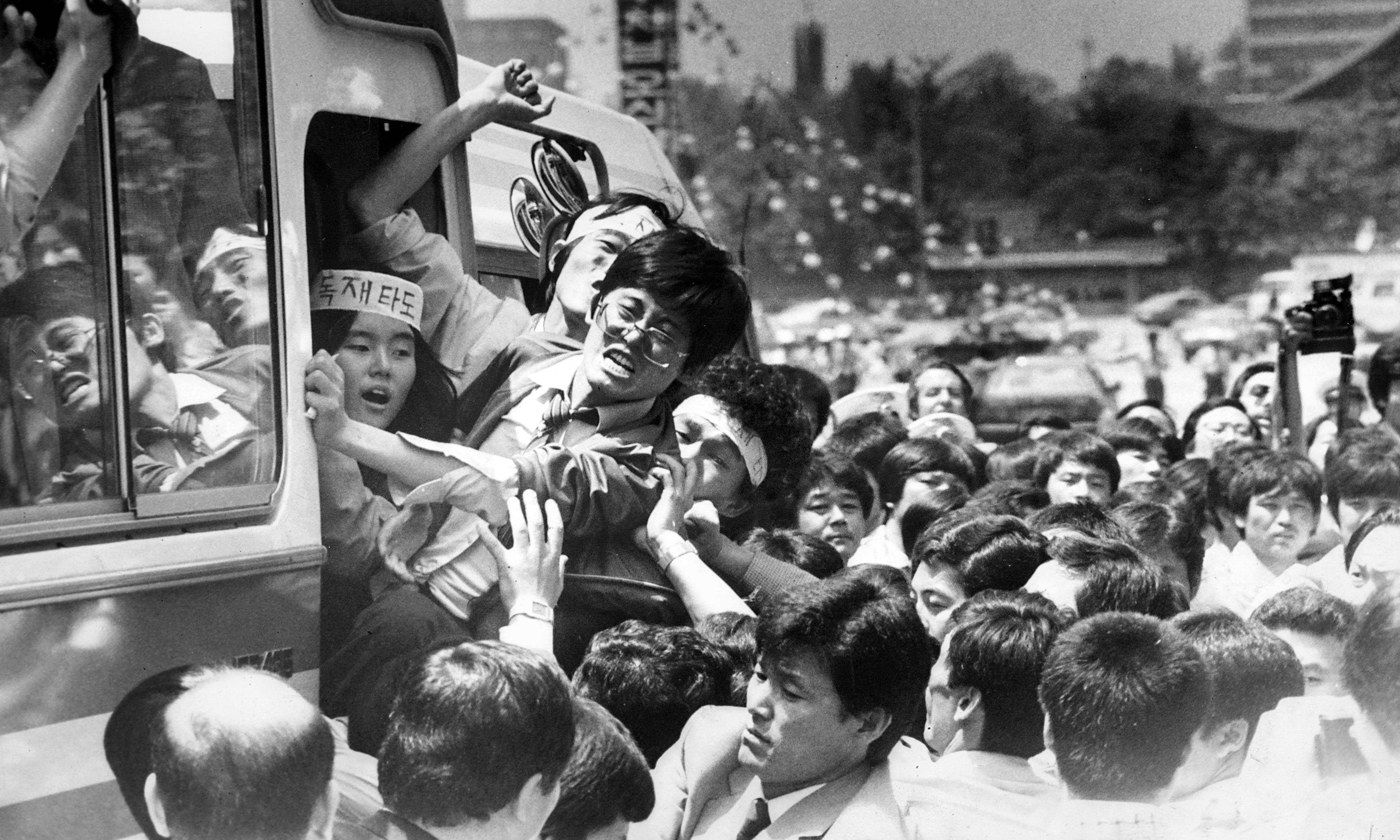

South Korea has experienced the presence of both extreme left-wing and extreme right-wing groups. The Northwest Youth Group, which was active between 1948 and 1953, belonged to the far-right. Meanwhile, the South Korean Workers’ Party during that time, along with leaders of student and labor movements in the 1980s and 1990s, were associated with the far-left. These groups employed violent methods and carried them out.

Examining the perspectives of men in their 20s–30s and older participants in the Taegukgi rallies, often associated with far-right views, shows no distinct far-right identity. There is no unified ideological structure or behavioral pattern—just a ‘temporary shift from individuals frustrated with the Democratic Party,’ nothing beyond that.

Go back to the time before martial law. News channels were overwhelmed with stories about President Yoon Suk-yeol, his wife, and Myung Tae-kyun interfering in the People Power Party’s selection process. The three quickly became topics of conversation in local taverns. Gallup Korea reported that Yoon’s approval rating before martial law was 19%, with an even lower 18% in the conservative region of Daegu and Gyeongbuk. Attendees at Taegukgi demonstrations at that time hurled harsh words at the presidential couple, angry that the person they voted for to beat Lee Jae-myung and the Democratic Party had turned into ‘bait’ undermining conservatism.

However, following the imposition of martial law, this situation changed suddenly. They stood behind Yoon’s narrative: “Martial law was introduced to combat the Democratic Party.” Endorsement of martial law and resistance to impeachment became automatic positions—not based on deep convictions, but rather a strong dislike for the Democratic Party. This reflected the pattern seen with “Moon supporters”—those who had excessively praised Moon Jae-in—turning against him once the People Power Party came into power, aligning with Lee Jae-myung’s enthusiastic young female followers, known as “Gaeddal” (“daughters of reform”) in their critiques.

The incident at the Seoul Western District Court is not unique. It was not driven by any particular values. During the 1980s, student movements frequently resorted to violence against U.S. cultural centers, party headquarters, courts, and police stations, often taking them over. These were not random actions but carefully organized under a communist ideology, in which the judiciary was seen as a ‘servant of capitalist power’ to be dismantled. Only such organized violence deserves labels like far-left or far-right. Just as smashing a police station window while intoxicated does not make someone far-right, the court incident was an impulsive act driven by group mentality—angry crowds demonstrating against Yoon’s arrest, not a planned action.

Recent demonstrations against China follow a similar pattern. They represent a reaction to President Lee Jae-myung’s appreciation for China. Should Lee adopt an anti-China position, these protests will diminish—similar to how members of the Democratic Party and devoted supporters, who previously stirred up anti-Japanese feelings through ‘Jukchangga,’ eased their rhetoric when Lee sought collaboration with Japan.

Men in their 20s to 30s share similar motivations. They are frustrated by the hypocrisy and inequity associated with the 586 generation (those in their 50s who were activists during the 1980s). Their frustration is directed at the Democratic Party, which they see as representing the 586 generation, rather than any specific ideology.

Certainly, extreme left and extreme right groups are present in South Korea. However, they represent a very small portion of the population and do not pose a risk to social stability. Their existence highlights the openness of South Korean democracy. Nevertheless, politicians’ tendency to label rivals as far-left or far-right is a way to avoid addressing their own shortcomings in ideas and policies. It serves as a method to bring supporters together by promoting strong opposition to the other side, and it’s an electoral approach that takes advantage of the public’s aversion to extremists. South Korea’s economy and society cannot afford to waste time on such performances.

Leave a comment