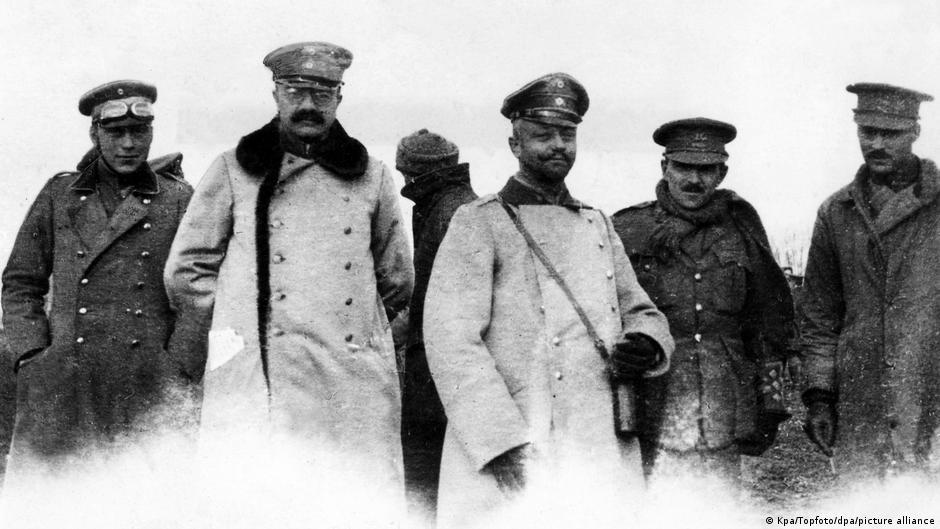

During the Christmas Eve of 1914, opposing German and British troops temporarily ceased hostilities and joined in singing Christmas hymns — a short-lived instance of tranquility amid conflict.

December 1914. World War I had been raging for five months. Between minefields and barbed-wire fences, millions of soldiers faced each other in trenches along the Western Front, occasionally as close as 30 meters apart. The area of conflict extended from the English Channel across Belgium and France up to the Swiss border.

As the conflict continued, troops gathered in their trenches, where rats, lice, the chill, and inadequate meals took a toll on them, with death constantly looming. Outside the trenches, in the area between the opposing forces, was the filthy nightmare of no man’s land, where the corpses of fallen friends remained inaccessible.

Disillusionment at the front

The conflict had already taken the lives of hundreds of thousands — British, French, Belgian, and German — destroyed by grenades, shot by machine guns, and killed in close-quarters bayonet fights. Many German troops had rushed into battle, convinced that victory was just ahead. They believed they would be back with their families by Christmas — at least that was whatGerman Emperor Wilhelm IIhad pledged. The French and British had also trusted their leaders when they claimed the soldiers would come back home soon. However, disappointment quickly took hold at the front line. Each day, the soldiers faced death directly, even on December 24. How could anyone feel festive under these conditions?

‘Silent Night, Holy Night’

Then something unexpected happened. In the middle of the freezing December night, a single German soldier in the trenches near the Belgian town of Ypres began singing “Silent Night.” More and more men joined in. The British on the other side of no man’s land could hardly believe their ears. “Silent Nightwas also widely recognized in England.

Initially, the British did not trust “the Hun,” a derogatory term they used for the Germans, and questioned if they were being tricked into a trap. However, they soon cheered and started singing along. The Germans replied with shouts of “Merry Christmas” and called out, “We won’t shoot, you won’t shoot!” The first courageous soldiers from both sides climbed out of the trenches, stood amidst the corpses of their fallen comrades, and shook hands.

Comparable scenes occurred across much of the Western Front. In Fleurbaix, close to the English Channel, German troops positioned ornamental Christmas trees at the edge of their trenches. The glowing lights were from candles, not gunfire.

Christmas trees, presents and football

The German military leadership arranged for thousands of trees to be sent to the frontline in an effort to lift soldiers’ spirits. Commanders understood the hardship faced by troops separated from their families on Christmas Eve.

Normally, having bright candlelight visible to the enemy went against strict rules, and prevented snipers from moving without being seen in no man’s land. That night, none of these concerns were relevant.

What I am about to share with you may seem unbelievable, but it is the truth,” wrote Josef Wenzl from the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 to his parents on December 28, 1914. “Between the trenches, fierce enemies were gathered around theChristmas treeand performing Christmas carols. I will never forget the scene for the rest of my life.”

Thousands of troops shared little presents that evening, swapping canned corned beef for sausages orDresden stollenFor plum pudding, they shared wine, rum, and cigarettes, and showed each other pictures of their brides, wives, and children. They exchanged uniform buttons as keepsakes. Most of the soldiers were British and German, though some French troops also participated in the truce, bringing out their stockpiles of champagne for Christmas.

They even played soccer, using German spiked helmets and British field caps as goalposts. A firm ball made of straw or a tin can was often used as the ball, although in certain areas the British managed to create an actual leather one. “We sent someone on a bicycle to the rear, to our reserve position,” a soldier from the Scots Guards wrote to his parents, “and he returned with the ball.”

A short-lived truce

There was another thing that held great significance for the soldiers on both sides: the opportunity to inter fallen comrades who had died in no man’s land. These were instances of compassion amidst a harsh conflict.

I’m not sure how much longer this will last,” young officer Alfred Dougan Chater wrote to his mother. “We’re certainly having another ceasefire on New Year’s Day, as the Germans want to check how the photographs turned out!

Not all individuals on the Western Front were inclined to interact with the opposing side. In certain regions, combat continued without interruption. This was precisely what high-ranking officers from both sides desired. They strongly opposed the Christmas Truce and considered such acts of camaraderie as unacceptable, even regarding them as a form of betrayal.

it is dreadful,” a german soldier later wrote to his family, “that one day you can communicate with each other peacefully, and the very next day you are forced to take each other’s lives.

Peace instead of war — a perfect vision?

World War I eventually resulted in the deaths of approximately 9 million soldiers, as well as many civilians. Josef Wenzl lost his life in combat on May 6, 1917 — two and a half years after he wrote to his parents: “Christmas 1914 is one I will never forget.” Over 100 years later, conflicts continue to occur across the globe — in Ukraine,Sudan and Congo. However, the soldiers of 1914 demonstrated how straightforward peace can be: Drop your arms and extend a hand to your adversary. Or is this merely an idealistic fantasy?

This piece was initially composed in German.

Author: Suzanne Cords

Leave a comment