The core of military operations is mobility, a concept that also applies to the role of a cook (once called a mess sergeant). In a short time, a 1-kilogram block of large square ham is cut into small pieces, forty-eight 400-gram cans of whelk are prepared, and a bag of anchovies for stir-frying is marinated with corn syrup and garlic. Within just over an hour, more than 300 portions of soup, rice, and three side dishes—including cabbage kimchi—are ready. In this kitchen that resembles a battlefield, what did I do? I sliced radish greens and ham with all my strength.

The history of military food supplies is extensive. As Napoleon once remarked, “An army moves on its stomach.” France has a saying: “Soup gives strength to the soldier.” Even basic and plentiful meals assist soldiers in enduring demanding operations.

In military units, personnel tasked with preparing meals are known as cooks. They were previously called mess sergeants, rapid-feeding soldiers, or supply sergeants, but the title has now been standardized. Since 1971, the South Korean military has managed its meal system by receiving food from external sources and having soldiers prepare them. Although the Ministry of National Defense has gradually allowed private companies such as Dongwon Home Food Co. and Our Home to provide meals to soldiers over the past three years, resulting in more “units without cooks,” the 54-year-old tradition of the cook specialty is not expected to vanish. Nevertheless, rumors like “we used an axe to break frozen ingredients for cooking” or “we practiced the five-grain rice principle every day” still persist. How are meals prepared in the military today? On the 11th, I accompanied a soldier with military specialty number 231107 at the Army’s 53rd Division “Chungryeol Unit” near Haeundae, Busan, to prepare breakfast and lunch.

◇A Morning Task in the Kitchen

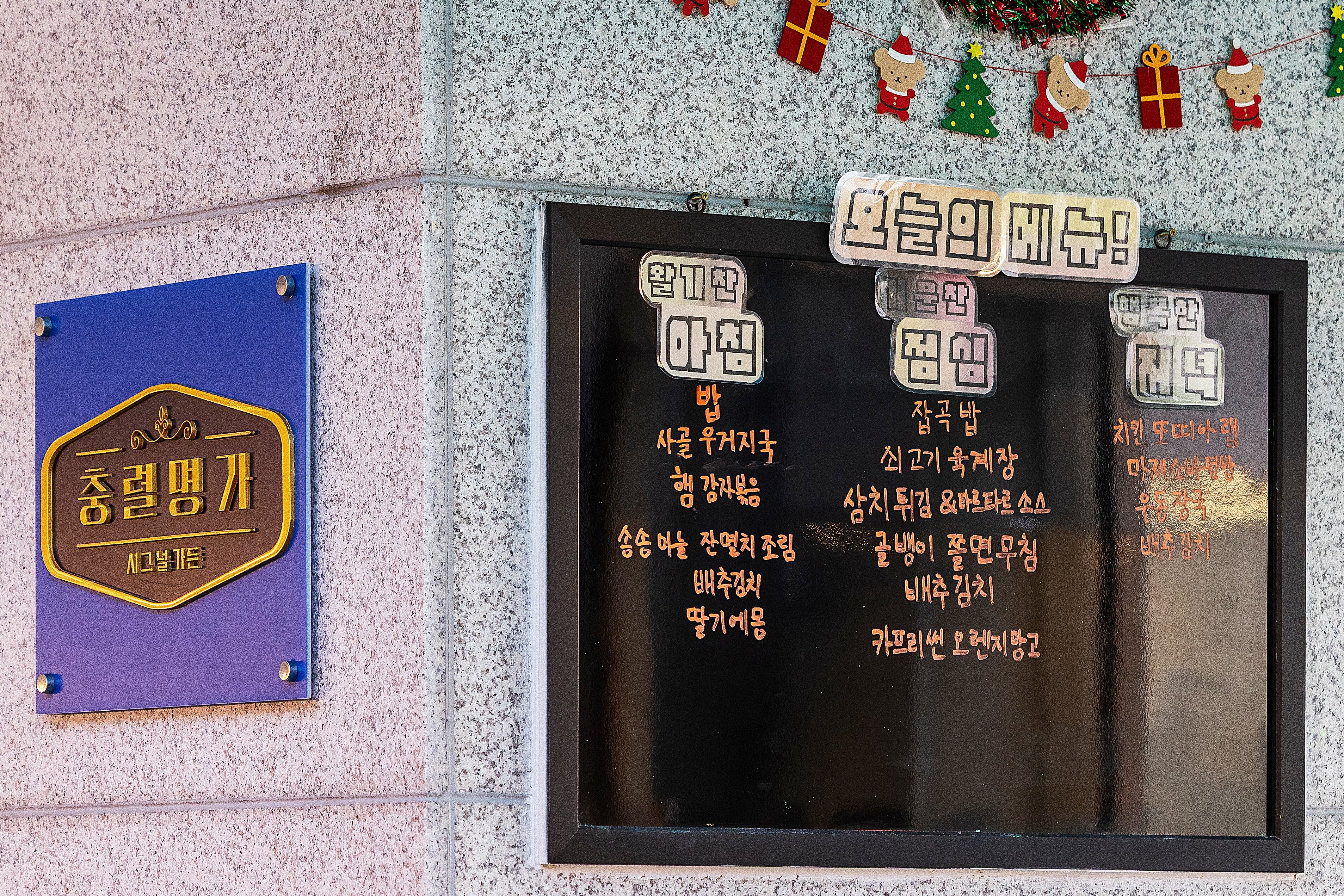

At 5:50 a.m., six individuals in dark uniforms quietly moved into a kitchen that was as large as a classroom. These were the elite chefs tasked with preparing three meals daily at the Chungryeol Unit’s dining area, known as “Chungryeol Myeongga” (House of Loyalty). Last year, Chungryeol Myeongga was recognized as the top unit in the Operations Command’s “Better Military Mess Hall” program.

The day’s menu included rice, radish green bone broth, ham and potato stir-fry, garlic-anchovy stew, cabbage kimchi, and strawberry-flavored milk as a treat. Sergeant Cho Hyun-joon, 25, who oversees the mess, assigned duties: rice preparation, soup making, stew cooking, stir-frying, cleaning dishes, and tidying the hall. “Safety and accountability are essential,” he mentioned. “If you don’t finish your task properly, you could lose ingredients or miscalculate the amounts.”

Right away, big ladles and massive woks shaped like shovels started to move. Every tool was big and weighty. The chefs operated like machines, saying nothing. I felt overwhelmed by the huge pile of ingredients. The large fridge was fully stocked with chili peppers, carrots, green onions, and other items, which were restocked and prepared every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Radishes, cabbages, and garlic had already been washed and peeled, so there was no need to peel the garlic.

Lee Hwa-sook, 59, the third-year kitchen supervisor and former kindergarten cafeteria employee, told me to cut the radish greens for the soup into thin slices. As I was cutting, another soldier was washing a large amount of rice in the sink before transferring it to a big steamer. He then combined barley, brown rice, and sticky rice with additional rice and washed them once more. Later, I found out that this mixture was prepared for the midday multigrain rice.

The kitchen was in disarray. Two woks designed for 150 servings hissed on big burners with potatoes, while more than 10 kilograms of pre-made bone broth packages were boiling in a 300-serving soup pot. Before I realized it, I was cutting ham. How did I get into this situation? The chef beside me cut ham twice as quickly as I could manage one slice.

The secret to cooking in bulk lies in the seasoning. Corporal Kim Eun-gu, 20, added about 2 kilograms of sliced radish greens and soybean paste into the soup pot, tasted it with a spoon, and then added chili powder and salt. “The seasoning hasn’t fully settled yet,” he mentioned. A graduate from the culinary department at Korea Hospitality Tourism Practical School, he also oversaw the lunchtime fish frying, seasoning it with pepper and sugar. There were 44 different condiments available, such as steak sauce, oyster sauce, and Nutella. This is the strength of a chef. The most demanding dish is fried food, which involves a struggle with hot oil. Morning was beginning in the kitchen.

◇Do Soldiers Still Enjoy Choco Pie?

No one was shouting “Delicious! Enjoy your meal!” while holding spoons upright. Around 7:30 a.m., soldiers took rice onto plates and ate simply. Even though self-service is permitted, a standard plate is positioned at the entrance to make sure no one leaves without food. “This portion ensures that everyone can eat,” said a cook. Observing the soldiers’ faces, far from their homes, I experienced an unexpected wave of emotion. Eat well—the radish greens and ham were cut by me.

As anticipated from hungry young men, meat-based meals are the most favored. A recent Army survey revealed 100% satisfaction with dishes such as frankfurter steak and vegetable bulgogi. On the other hand, 14% and 25% of soldiers “strongly disliked” seaweed soup with rice balls and soup with rice, respectively. If “like” and “dislike” are equally divided at 50%, the meal is usually removed from the menu due to too many leftovers. A typical example is spicy braised chicken. There is also a “brunch day” every two weeks, giving soldiers the chance to enjoy franchise foods like burgers on base.

After the cleaning is done, the cooks have some personal time until approximately 9:50 a.m. “Do soldiers still enjoy Choco Pie?” I asked, as someone who isn’t a veteran from an older generation. Private Oh Do-hyun, 20, sighed, “Now there’s the military store (PX), which is a great place…” He is a graduate of the K-Food Culinary Department at Osong Information High School and aspires to become a chef. “Large rotating pots aren’t used in restaurants or schools,” he said. “Here, I’ve learned to estimate ingredient quantities and improved my knife skills.” Dealing with a variety of ingredients is also a benefit.

Cooks rise 40 minutes before standard soldiers, at 5:50 a.m., and complete their tasks around 7:00 p.m., 30 minutes later. Because of minimum staffing rules, they are only allowed to take leave once every three to four months. When asked about difficulties, Corporal Kim Min-jun, 21, responded without hesitation, “It was tough at first, but the senior members taught me well, and I’m getting by!” The soldier-like, energetic response touched me. I know you miss home—just keep going a little longer.

◇Understanding the Environment Is Essential in Both Society and the Military

Silent efficiency returned during lunch preparation. The menu included multigrain rice, spicy beef soup, fried mackerel, spicy whelk noodle salad, and Capri Sun orange-mango juice as a treat. Private Park Do-hyun, 21, was responsible for maintaining cleanliness. He continuously sprayed water from a hose, scrubbing big soup pots and woks. Five minutes later, he was cleaning another rotating pot. Cooking and dishwashing occurred at the same time—utensils were cleaned right after use, ensuring no dishes accumulated later. Yellow gloves were used for cooking, while pink ones were for washing dishes. Each time someone forgot to change gloves, the hygiene enforcer would quietly say, “Rubber gloves.”

Although there was no set path, the pace was incredibly fast. One soldier opened can lids, another emptied them, and a third silently disposed of them. A basin for whelk was prepared just in time. “How do you know what to do so quickly?” I asked quietly while cutting the whelk. “By reading the room?” Private Lee Soo-hwan, 21, smiled and rushed off to add three ladles of anchovy sauce to the spicy soup. Indeed, it all came down to instinct. Because of this, I had more tasks than during breakfast—tearing noodles, stirring pots, and washing dishes as soon as they were used.

As the soldiers operated like ninjas, I had very little to do. I wanted to assist but wasn’t able to. On our way out, I asked, “Don’t you miss your parents?” which brought tears to their eyes. Even though they have phone access after their shifts, nothing compares to seeing their families in person. Private Lee Soo-hwan, who joined in July and hasn’t taken leave yet, said, “I hope to stay healthy here and see them soon.” Private Oh Do-hyun added, “I always miss my parents.” Our soldiers silently carry out their duties—stay healthy and come back safely. And to the approximately 11,000 cooks responsible for feeding the military, keep up the good work!

Leave a comment