American researchers have, for the first time, created early-stage human embryos by modifying DNA obtained from individuals’ skin cells and subsequently combining it with sperm.

The method may address infertility caused by aging or illness, utilizing nearly any cell in the body as the foundation for creating life.

It might also enable same-sex couples to have a child who is genetically connected to them.

The approach needs substantial improvement – a process that might span ten years – before a fertility clinic would even think about implementing it.

Experts noted it was a remarkable advancement, yet there was a need for an open dialogue with the public regarding what science was enabling.

The process of reproduction was once seen as a straightforward tale of a man’s sperm combining with a woman’s egg. They merge to form an embryo, and after nine months, a baby is born.

Currently, researchers are altering the guidelines. This new study begins with human skin.

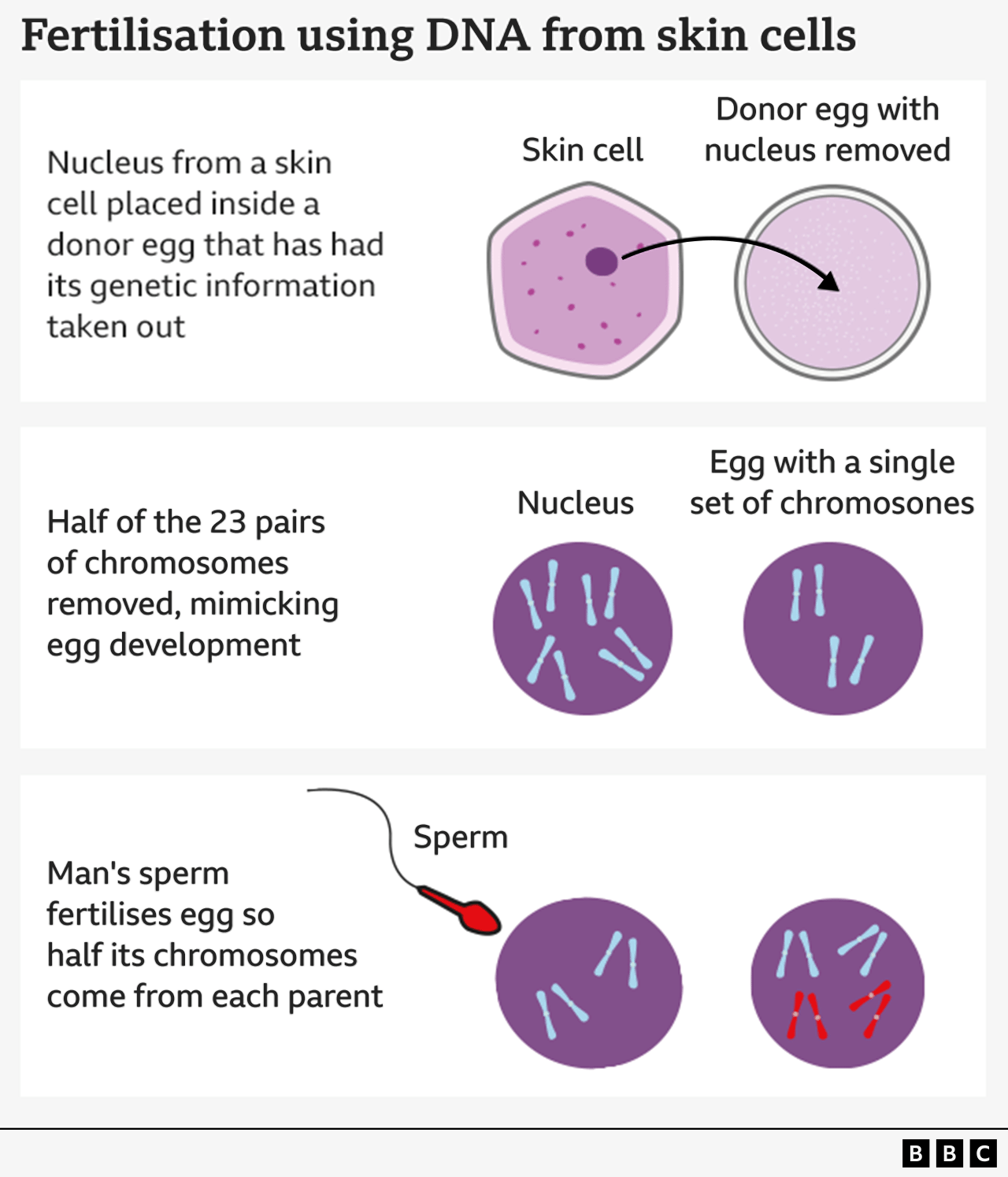

The research group from Oregon Health and Science University’s method involves removing the nucleus, which contains a copy of the complete genetic information required to form the body, from a skin cell.

It is subsequently inserted into a donor egg that has had its genetic information removed.

So far, the method resembles the one employed to produce Dolly the Sheep—the first cloned mammal in the world—which came into existence in 1996.

Nevertheless, this egg is not prepared to be fertilized by sperm since it already has a complete set of chromosomes.

You receive 23 of these DNA groups from each parent, making a total of 46, which the egg already contains.

Therefore, the following step involves convincing the egg to eliminate half of its chromosomes through a process that the scientists have called “mitomeiosis” (a term combining mitosis and meiosis, the two methods by which cells divide).

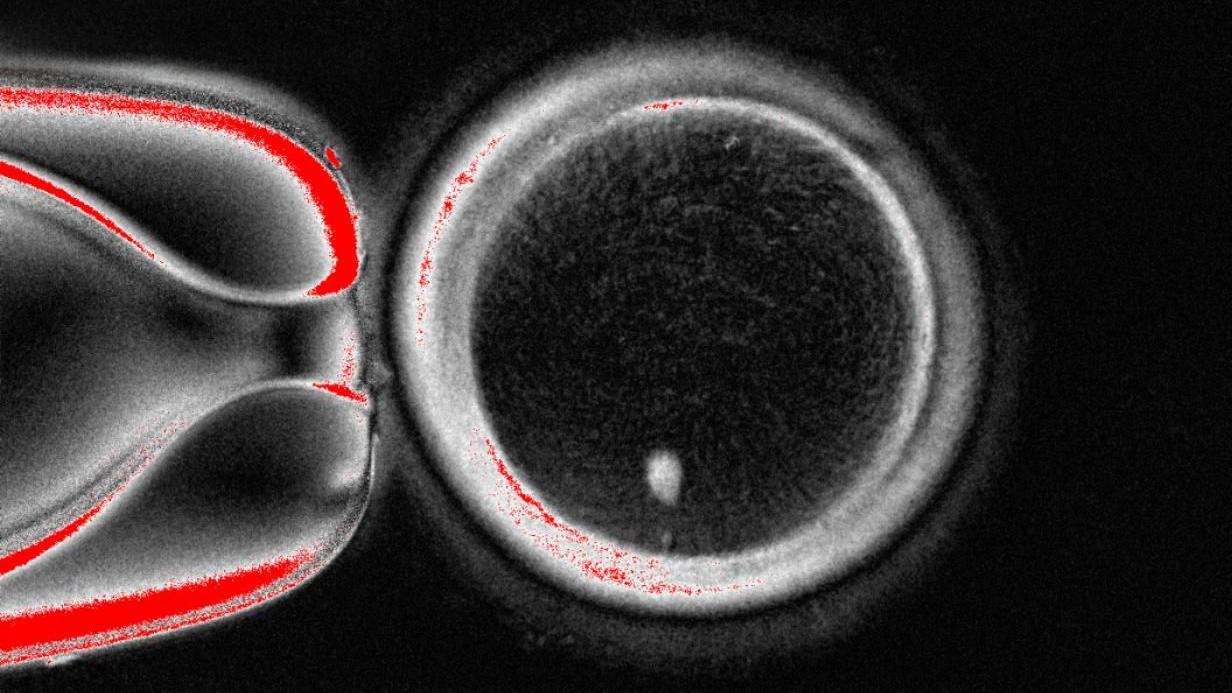

The study, appeared in the journal Nature Communications, demonstrated that 82 functional eggs were produced. These were fertilized with sperm, and some advanced to the early stages of embryo development. None developed beyond the six-day stage.

“We accomplished a feat that was considered unattainable,” stated Prof Shoukhrat Mitalipov, the head of the Oregon Health and Science University’s center for embryonic cell and gene therapy.

The method is not yet refined, as the egg randomly decides which chromosomes to eliminate. It should end up with one of each of the 23 types to avoid illness, but instead ends up with two of some and none of others.

There is also a low success rate (approximately 9%), and the chromosomes fail to undergo a crucial process in which they reorganize their DNA, known as crossing over.

Prof Mitalipov, a world-renowned pioneer in the field, told me: “We have to perfect it.

Eventually, I believe that’s where the future is heading since an increasing number of patients are unable to have children.

This innovation is part of an expanding area of research focused on creating sperm and eggs in a laboratory setting, referred to as in vitro gametogenesis.

The method remains in the stage of scientific exploration rather than practical medical application, yet the goal is to assist couples who cannot undergo IVF (in vitro fertilization) due to a lack of sperm or eggs.

It may assist older women who no longer have viable eggs, men who do not generate sufficient sperm, or individuals who have become infertile due to cancer treatment.

The area also changes the guidelines of being a parent. The method discussed today is not limited to using a woman’s skin cells – it could alternatively use a man’s.

This creates the possibility for same-sex couples to have children who are genetically connected to both partners. For instance, in a male same-sex relationship, one man’s skin cells could be utilized to create an egg, while the other partner’s sperm could be used for fertilization.

“Besides providing hope for millions facing infertility caused by a lack of eggs or sperm, this technique could enable same-sex couples to have a child who is genetically connected to both partners,” stated Prof Paula Amato, from Oregon Health and Science University.

Build public trust

Roger Sturmey, a reproductive medicine professor at the University of Hull, described the research as “significant” and “remarkable.”

He stated: “At the same time, this kind of research highlights the significance of maintaining open communication with the public regarding recent developments in reproductive science.”

Events like this highlight the importance of strong oversight, to guarantee responsibility and foster public confidence.

Professor Richard Anderson, deputy director of the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health at the University of Edinburgh, stated that the capacity to create new eggs “would represent a significant breakthrough.”

He stated: “There will be significant safety issues, but this research represents a progress in enabling numerous women to have genetically related children.”

Leave a comment